by Lawrence Broxmeyer, MD

© 2012 All Rights Reserved ; Registered: US Library of Congress

Lawrence Broxmeyer, MD, is a Pennsylvania internist and medical researcher. He was on staff at New York affiliate hospitals of SUNY Downstate, Cornell University, and New York University for approximately fourteen years. In conjunction with colleagues in San Francisco and at the University of Nebraska, he first pursued, as lead author and originator, a novel technique to kill AIDS mycobacteria and tuberculosis, producing outstanding results [see Journal of Infectious Diseases 186, no. 8 [October 15, 2002]: 1155––60]. Recently he contributed a chapter regarding these findings to Sleator and Hill’s textbook Patho-biotechnology, published by Landes Bioscience. In addition, Broxmeyer has written many peer-reviewed articles, available on PubMed of the US Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=broxmeyer%20L. Broxmeyer’s research covers the most challenging medical problems of our times, including AIDS, Alzheimer’s disease, Diabetes, Parkinson’s and cardiovascular disease. Among the books that Dr. Broxmeyer has published is AIDS: What the Discoverers of HIV Never Admitted ISBN-10: 1890035297 ISBN-13: 978-1890035297 : 81 pages Publisher: New Century Press; 3rd edition (February 18, 2003).

The manuscript below AIDS and the “HIV” Hypothesis, is an adaptation of this AIDS book as well as peer-reviewed articles done by Dr. Broxmeyer. Excerpts from reviews regarding Broxmeyer’s AIDS book are below:

“I am of the opinion that this book may offer a solution to the mystery surrounding the AIDS pandemic with regards to a possible vaccine or cure for AIDS in the near future.

Finally the author should be congratulated for “daring where Angels feared to tread.”

-PROFESSOR P S IGBIGBI

“I have never learned so much in such a short time – your book, “AIDS : What the Discoverers of HIV Never Admitted”, is absolutely the most revealing and clearly documented work I’ve ever read! Talk about a superb journalistic documentary –amazing.”

-DOUGLASS ALEXANDER, PhD

“ I think you are a PIONEER…………..YOU have to make the discoveries because apparently no one has gone there before you!! Sometimes the best beginning discoveries are the people who ask the controversial QUESTIONS that cast doubt on the status quo. Like WHAT IF?????”

-ALAN CANTWELL JR., MD

INTRODUCTION:

Once upon a time, a small group of politically powerful scientists rammed a flawed theory on the origin and cause of AIDS down America’s and then the world’s throat.

Yet we are still led to believe that we are fortunate, even ‘lucky’ that retroviruses, only discovered in the 1970s, were uncovered just in time to label them the culprit in a killer AIDS epidemic. And ‘lucky’ that two ‘HIVs’ were discovered in rapid succession and the technology and theory to link AIDS to the ‘HIV’ retrovirus were fully in place, for the first time in history, only a few years prior to the recognition of the AIDS epidemic.

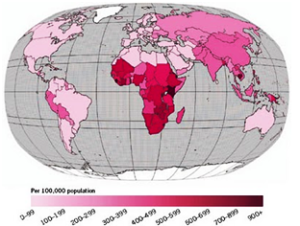

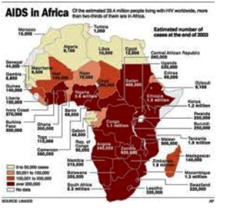

Lucky? Even as of the 20th anniversary of the first reported AIDS cases passed, AIDS had infected nearly 60 million people of which almost 22 million, including nearly half a million Americans died, and 8,500 AIDS deaths occurred daily. Yet the prospects for a cure or vaccine are as remote as they were three decades ago.

And according to one website, almost 3,000 scientists, doctors and educators have expressed doubts, on the makeshift, contrived evidence to this point provided that “HIV” causes AIDS.

(http://www.rethinkingaids.com/quotes/rethinkers.htm).

Nevertheless, the mantra that “HIV is the sole cause of AIDS” is so well-known and accepted universally that any suggestion to the contrary is usually met with disdain by the AIDS establishment. One notable example of this disdain was provided by Taiwanese-born TIME magazine’s Man of the Year in 1996, AIDS researcher David Da-i Ho MD[1], who famously and absurdly declared: “It’s the virus, stupid!”

Despite such blather, it is important to realize that the statement “HIV is the sole cause of AIDS” is just a hypothesis. There are unanswered questions and controversy concerning the role of HIV “as the sole cause of AIDS.” And until they are resolved, a cure is not possible.

First, let me say that having practiced treating AIDS patients and done AIDS-based research during and after the deadly US AIDS coastal epidemic, with peer-reviewed studies to that effect, including one which landed in the Journal of Infectious Diseases — it is inconceivable to me that anyone can address the question of AIDS origin without seeing that it began as a highly transmittable infectious disease which could be sexually transmitted.

Let me assure you, to think differently is merely to box oneself into a scientifically untenable position. The case of Gaëtan Dugas alone, the French-Canadian Air Canada flight attendant who single-handedly infected either by himself, or through his sexual contacts, 40 new cases AIDS, speaks differently — much differently.

On the other hand the growing number of scientists that doubt that the HIV retrovirus or any other retrovirus could not be behind the AIDS epidemic, stand on firm ground.

So reasonable is the latter assumption, in fact, that eventually Dr. Luc Montagnier himself, HIV’s primary discoverer, came out with his ‘cofactor’ theory, which basically admitted that HIV in and of itself could not even approach the destruction rendered in AIDS patient.

AIDS picture: dying man

So the emphasis here, and I might add, the only correct emphasis to pursue, will not be whether AIDS can be caused by an infectious factor, but whether the so-called “HIV virus” is really a virus or retrovirus to begin with.

AIDS One HIV regimine, supposedly ‘antiretroviral’, like the pills in this patient’s hand, seemingly keep AIDS at bay, but can take a harsh physical toll.

One argument often used by HIV pharmaceutical-sponsored devotees is to show how their antiretrovirals increase life spans of AIDS victims. But does antiretroviral therapy [HAART] really prolong lives? Depends upon how you look at it. To some orthodox believers, yes, by an average of 13-15 years. To others, this is absurd —citing that the rate of death among “HIV/AIDS” was just being increasingly redefined by the HIV powers that be to include illnesses less life-threatening than that behind the original AIDS epidemic.

Yet, though HAART might or might not greatly prolong life on the average, there is at least some reliable testimony that individuals have experienced clinical improvement on it, often dramatic and immediate. However logic insists that such immediate benefit cannot be the result of any antiretroviral action, whose supposed benefits [decrease in ‘viral load’, rise in CD4] come slowly. Rather such testimony likely reflects an antibiotic or anti-inflammatory effect.

If such antiretrovirals are indeed exerting an antibiotic affect, the question then becomes :which microorganism [and not virus] are the they hitting? Kirk et al reported that antiretrovirals cause a marked decrease in the incidence of TB and to an even larger extent the fowl tuberculosis (Mycobacterium avium), which many experts consider inevitable with AIDS. [2] And unlike what the manufacturers of such antiretrovirals would like to hear, Kirk was hard pressed to explain the significantly lower risk of fowl tuberculosis in AIDS to merely an increased CD4 immune cell count. Rather such a dramatic drop in tubercular mycobacterial avium suggested to him a direct affect on the part of “antiretrovirals” against AIDS-borne fowl tuberculosis.

This opens up the interesting question as to whether “antiretorvirals” aren’t acting more like poorly designed, super-expensive, anti-tubercular agents and increasing CD4 counts merely by suppressing typical and atypical forms of TB. It has always been terribly important to pharmaceutical interests to give the impression to both lay and scientific community alike that their antiretrovirals, and only their “antiretrovirals”, could increase a CD4 immune count in AIDS patients. Yet we know that one of the most dramatic restorations of CD4 count on record occurred in patients with “HIV” and TB when only anti-TB treatment was used — in John’s study where a CD4 count of 89/ll climbed to 760/ll. [3] This of course doesn’t fit into Big Pharm’s agenda, as all anti-tb antibiotics are now off patent and cannot generate nearly the profit of their antiretrovirals.

Just as disconcerting to American pharmaceutical interests was the unexpected find in early AIDS autopsies of the surprisingly high proportion of difficult to diagnose fowl tuberculosis or Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare, [4] in up to 55% of American cases in early studies. [5] In all likelihood this American percentage was much higher as statistics used did not include respiratory and gastrointestinal colonization without clinically evident infection. According to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, TB is still the major attributable cause of death in AIDS patients.

Pharmaceutical interests could not just ignore this, so they began publishing studies which showed, how with antiretrovirals, tubercular infection dramatically [6] declined. [See Figue 1]

![AIDS Figure 1 Incidence of Disseminated Fowl tuberculosis [Mycobacterium avium Complex] Infections in US AIDS. The HIV Outpatient Study 1994-2007.](https://lawrencebroxmeyermd.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/aids-pic-figure-1-incidence-of-disseminated-fowl-tuberculosis-mycobacterium-avium-complex-infections-in-us-aids-the-hiv-outpatient-study-1994-2007.png?w=300&h=168)

Figure 1. Incidence of Disseminated Fowl tuberculosis [Mycobacterium avium Complex] Infections in US AIDS. The HIV Outpatient Study 1994-2007.

Figure is based on data from Buchacz K, Baker RK, Palella FJ Jr, et al. AIDS-defining opportunistic illnesses in US patients, 1994-2007: a cohort study. AIDS. 2010;24:1549-59.

The purposeful loosening of criteria by HIV scientists to include tuberculosis —which infects, according to the CDC, a third of the world — as well as fowl tuberculosis as “AIDS-defining” illnesses was simply a survival strategy to keep the HIV hypothesis viable. HIV diehards early realized that up to 70% of people with TB were “HIV-positive”. And although there were other “AIDS-defining” illnesses postulated, none came close to the number of people infected by TB. Besides, early HIV investigators knew very well that not only were tubercular mycobacterial infections the main cause of bacterial infection during AIDS; but that they often preceded other infections in AIDS by 1–10 months. [7]

So above all, tuberculosis had to be made an “AIDS-defining” illness. In fact the definition of HIV now, thanks to their active efforts, became so loosely constructed that even patients with verifiable tuberculosis and no HIV, but who nonetheless reacted positively for HIV, could be incorporated under the umbrella of having AIDS despite the fact they didn’t have HIV.

No more was the hypersensitivity, and evasive tactics of “HIV experts” on display towards tuberculosis and its related mycobacteria than in the 2005 book entitled Retroviral Testing and Quality Assurance Essentials for Laboratory Diagnosis [8]. Here forgetful “HIV experts” left out on page 24 TB and its related mycobacteria from their list of “medical conditions” suspected or known to produce false-positive screening and Western blot tests in AIDS. Included among these “experts” were those from the University of Maryland’s Viral Diagnostics, The Institute of Human Virology, The FDA, the Director of the National Serology Reference laboratory in Australia, the World Health Organizations [WHO] and the Centre on HIV/AIDS [also in Australia].

And the fact that this entire group studiously ignored what is hands down the biggest cause of such AIDS false-positive screening tests and “indeterminate” Western Blots didn’t even seem to faze them. Moreover, that this was oversight on the part of these “HIV experts” is extremely doubtful if one knows the history involved.

Veterinarian Max Myron Essex, a key figure in early “HIV” research.

Well-known since the first scientist to propose HIV testing — Veterinarian Max Myron Essex — tuberculosis gives a false positive for “HIV” in almost 70% of cases. In fact such cross reactivity between “HIV” and tubercular pathogens was so significant that it forced Essex and his colleague Kashala to warn that both the HIV screening test [ELISA] and Western Blot results “should be interpreted with caution when screening individuals with M. tuberculosis or other mycobacterial species.” [9] This of course automatically meant throwing away HIV serum diagnostics for at least 1/3 of the people in the known world — and that fraction doesn’t even include M. avium, the fowl tuberculosis also so common in AIDS.

ELISA HIV AIDS Test Screening

AIDS Western Blot Test to confirm the person is HIV positive.

But there were other problems in the proclamation that AIDS antiretrovirals extended lives an average of 15 years. And they soon became apparent. While the original AIDS patients were desperately ill, many of them showing fowl tuberculosis early in their disease, presumably through rectal transmission……….as time went on not all cases of “AIDS-defining” TB were ill, many of them being dormant or asymptomatic. Such AIDS individuals would survive longer. In the meantime, with all the literature touting that antiretrovirals increase the life of AIDS patient, with or without such drugs, the greatest risk of death [median age] from “HIV” disease remains 35-45 years-old, much as when AIDS began.

And then there was the terrible toxicities of these antiretrovirals. The fact that certain studies claim that antiretrovirals extend the life of an AIDS patient does not mean that they are benign in the least. As just one example, and putting aside the black box warnings regarding liver failure, kidney failure and severe neuropathy — many cardiac complications of HIV are not affected by antiretroviral cocktails [HAART] and such heart problems continue to develop in AIDS either with antiretroviral treatment, or because of antiretroviral treatment. This is because viral treatment itself can cause a metabolic syndrome, characterized by altered body-fat distribution and an insulin resistance. This together with other factors that such retroviral cocktails create are associated with increased atherosclerosis and subsequent risk of peripheral artery and coronary artery diseases such as heart attacks. [10]

Also in the HIV Positive population of patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), there has also been an increase in the incidence of severe facial lipoatrophy [facial wasting], at times quite grotesque.

AIDS Facial lipoatrophy from antiretrovirals.

In 2000, French retrovirologist Luc Montagnier, at least the co-discoverer, and in the eyes of many, the discoverer of HIV — who seldom saw a retrovirus that he didn’t feel was either infective or lethal to humans — said:

“it is tuberculosis that constitutes the greatest public health problem today: 1.7 billion people have latent infections of Mycobacterium tuberculosis [the bacillus that causes tuberculosis], while eight million are actively infected.” [11] Actually in 1990, tuberculosis killed more people than any other single disease – almost 3 million.

Perhaps, it might have been better, therefore had Montagnier redirected his thoughts into his hypothesized retroviral cause of AIDS. For example:

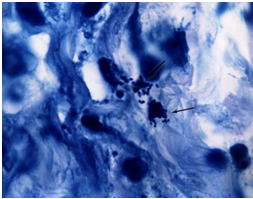

The first reports of fowl tuberculosis in US AIDS appeared in 1982, the year previous to Montagnier and Barré-Sinoussi’s, original Pasteur report on their mysterious retrovirus. At UCLA Zakowski [12] found that “all of the homosexual patients that have died of acquired immunodeficiency at the UCLA Medical Center for the Health Sciences have had disseminated MAC [fowl tuberculosis] infection.” Furthermore, the team mentions: “Because of this preliminary observation, we now vigorously seek evidence of mycobacteria [tubercular] infection in homosexuals with unexplained lymphadenopathy [a disease, disorder or enlargement of the lymph nodes].” Zakowski, in fact mentions that he did not feel it unreasonable to treat AIDS patients empirically for fowl tuberculosis”, pending the results of mycobacterial cultures, even if acid-fast [tubercular] bacilli are not identified on smears or tissue sections.” In fact, in the eyes of Zakowski and his colleagues, such anti-tubercular treatment could very well be life-saving.

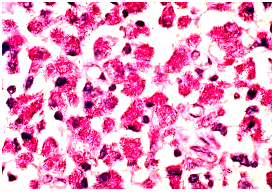

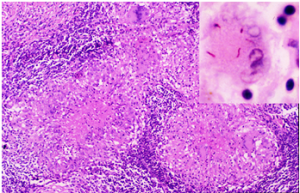

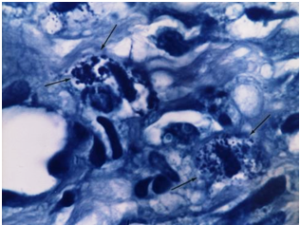

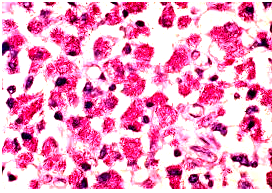

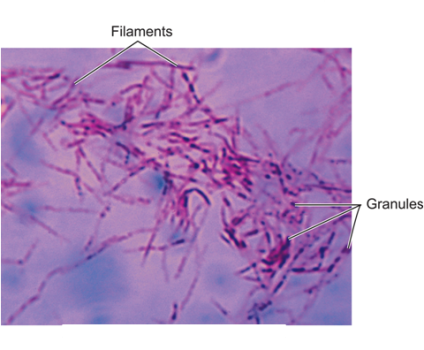

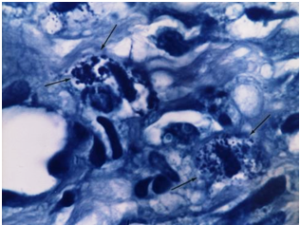

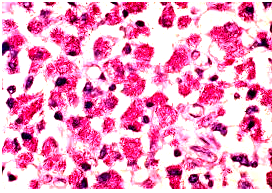

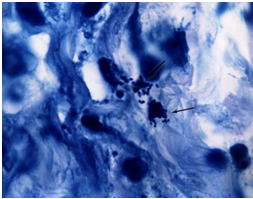

Mycobacterium avium in lymph node tissue of

an AIDS victim. Ziehl-Neelsen stain. Histopath-

ology of lymph node shows tremendous numbers of acid-fast tubercular bacilli within plump histiocytes. CDC/Dr. Edwin P. Ewing, Jr.

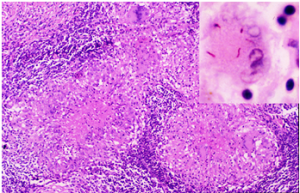

Tuberculosis of a lymph node (lymphadenopathy) in the neck.

Microscopic picture of TB of the lymph node. In the right upper corner insert are classical red (acid-fast) tubercular bacilli.

Therefore one can only wonder why Luc Mantagnier not only ignored but didn’t even consider this disease before sending Françoise Barré-Sinoussi in with his human HIV-reverse-transcriptase Geiger counter to look exclusively for a “retrovirus” in the white blood cells called lymphocytes taken from the enlarged lymph nodes of their first case of “HIV” — a young gay man sick with AIDS. After all, these first French AIDS specimens, taken in 1983 had a medically indicated differential diagnosis protocol to follow. In fact, soon thereafter McCabe appeared [13] in The Journal of the American Medical Association [JAMA], offering that not only did TB clearly preponderate as the cause of enlarged lymph nodes in adults, but that atypical TB, such as Mycobacterium avium [fowl TB] was hands down the number one cause of infectious lymph node involvement in children. Shouldn’t this have given Montagnier and Françoise Barré-Sinoussi pause to test for such pathogens before attributing these first French AIDS lymph nodes specimens exclusively to a “retrovirus”? Apparently not, as not even the mention or afterthought of tuberculosis or fowl tuberculosis [M. avium] was in their report.

And yet despite this, TB and Fowl TB were the two leading causes of infectious death in AIDS, both having bacillary [or a bacillus form] as well as viral forms — every bit as capable of throwing off signals for the reverse transcriptase registering on Montagnier and Françoise Barré-Sinoussi’s equipment as retroviruses were.

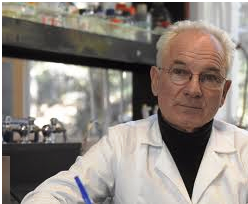

AIDS Virologist Françoise Barré-Sinoussi

From its first publication, “HIV” was questionable. Biochemist Kary Mullis, who in 1993 was ironically awarded his Nobel Prize for his work with the Polymerase Chain Reaction [PCR] used in HIV detection said:“If there is evidence that HIV causes AIDS, there should be scientific documents which either singly or collectively demonstrate that fact, at least with a high probability. There is no such document.”

And to Dr. Heinz Ludwig Sanger, Emeritus Professor of Molecular Biology and Virology, Max-Planck-Institutes for Biochemistry, Munchen said that it had become obvious that: “Up to today there is actually no single scientifically really convincing evidence for the existence of HIV. Not even once such a retrovirus has been isolated and purified by the methods of classical virology.”

The meticulous research of the Perth Group best summed things up:

“What we are doing and have been doing from the very beginning is to question the accepted cause of AIDS and to put forward an alternative theory for the cause of AIDS which has a number of well-defined predictions, most of which have been satisfied.”[14]

“Since in our view at present no evidence exists that AIDS is caused by a retrovirus, we see no reason for AIDS patients to be treated with antiretroviral drugs. We did write a critical analysis on the use of AZT as an antiretroviral agent when we showed that, given its pharmacological properties, it is not possible for it to have an antiretroviral effect. We have also presented evidence that AZT and nevirapine do not prevent mother-to-child transmission. However, we never advised that antiretroviral drugs should never be prescribed since up till now the possibility had not been excluded that they may have clinical benefits acting by means other than as antiretroviral agents. However, given the latest publication on HAART, this may not be the case.”

The thesis of this paper is that what is called “HIV” is in reality viral forms of cell-wall-deficient atypical tuberculosis complicating a picture of earlier exposure and acquisition of a tubercular infection, active or latent. Such previous infection could have occurred at any time in the life of an individual, and most often does so in the formative years. But when existing tubercular infection is then coupled with extremely virulent atypical tubercular forms [such as M. avium] commonly found in US AIDS, this deadly one-two punch of immunosuppression sets the stage for the real so-called “opportunistic” infections that also jump on board in AIDS. Furthermore, if the antiretrovirals have any benefit towards the extension of the life of an AIDS patient, which some reports claim is an average of 15 years, this has little to do with their action against “HIV” and a lot to do with the fact that such antiretrovirals, though mechanisms still being worked out, serve to suppress the two leading causes of infectious death in AIDS: Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium. It will also be shown that even the use of these antiretrovirals still apparently is not enough to prevent tubercular pathogens from being the leading cause of death, even in societies with free access to such HIV antiretrovirals. [15]

- Ho DD, Neumann AU, Perelson AS, Chen W, Leonard JM, Markowitz M: Rapid turnover of plasma virions and CD4 lymphocytes in HIV-1 infection. Nature 1995, 373:123-126.

- Kirk O et al Infections with Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium among HIV-infected Patients after the Introduction of Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2000Vol. 162: 865-872.

- John J. J., Kaur A. Tuberculosis and HIV infection. Lancet 1993; 342(2): 676.

- Welch K., Finkbeiner W. Autopsy findings in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. JAMA 1984; 252:1152–1159.

- Kiehn T. E., Edwards F. F. Infections caused by Mycobacterium avium complex in immunocompromised patients: diagnosis by blood culture and fecal examination, antimicrobial susceptibility tests, and morphological and seroagglutination characteristics. J Clin Microbiol 1985; 21:168–173.

- Buchacz K, Baker RK, Palella FJ Jr, et al. AIDS-defining opportunistic illnesses in US patients, 1994-2007: a cohort study. AIDS. 2010;24:1549-59.

- Bisburg E. Central nervous system tuberculosis with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and its related complex. Ann Intern Med 1986; 105: 210–213.

- Constantine NT, Callahan JD, Watts DM. Retroviral testing: essentials for quality control and laboratory diagnosis. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, 1992:117-118.

- Kashala O, Marlink R, Ilunga M, et al. Infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and human T cell lymphotropic viruses among leprosy patients and contacts: correlation between HIV-1 cross-reactivity and antibodies to lipoarabinomannan. J Infect Dis 1994; 169:296-304

- Barbaro G, HIV infection, highly active antiretroviral therapy and the cardiovascular system Cardiovascular Research 60 [2003] 87-95

- Montagnier L Virus New York WW Norton & Company, Inc, 2000.

- Zakowski P., Fligiel S. Disseminated Mycobacterium avium- intracellulare infection in homosexual men dying of acquired immunodeficiency. JAMA 1982; 248: 2980–2982.

- Lai KK, Stottmeier KD, Sherman IH, McCabe WR. Mycobacterial cervical lymphadenopathy: Relation of etilogic agents to age. JAMA 1984; 251:1286-1288.

- Papadopulous-Eleapulos E, Turner VF The Perth Group Challenges John Moore. Rethinking AIDS Sept 23, 2006 http://www.rethinkingaids.com/challenges/Moore-Perth.html

- Saraceni V et al. Tuberculosis as primary cause of death among AIDS cases in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Int. J. Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008, 12(7):769-772.

EPIDEMIC

Manhattan, 1979

By 1979, doctors in Manhattan began to notice a strange new disease killing what had been up to then healthy gay men. As reports mounted, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) was forced to circulate similar notices of homosexual men in New York and Los Angeles with a weakened immune system dying from heretofore rare causes. [1]

The first AIDS cases were uncovered in Manhattan in 1979.

From its conception AIDS was a nightmare of anguished victims, washed with wave after wave of terrible disease, whose physicians, like so many medical priests, helplessly watched them die. U.S. Coastal hospitals in San Francisco, New York and Los Angeles soon turned into war zones.

The strange disease lurked among the gay habitual visitors of bathhouses. Men began dying of pneumonia and other respiratory illnesses, but only after drastically losing weight and developing horrific skin lesions on their faces, necks, backs, and chests. This disease became known in the gay community as “gay cancer”. It was particularly volatile, and it progressed rapidly.

As more cases of the mysterious killer emerged, the name was changed from “gay cancer” to “gay-related immune deficiency” (GRID). This, at least, was an open recognition that whatever was causing the disease was compromising a body’s immune system. It didn’t explain, however, the rather esoteric choice of gay men, [and soon discovered] IV drug users as victims. Gay men realized the danger. Many made the intuitive leap early that perhaps certain activities, such as anal intercourse, might be transmitting the causative agent.

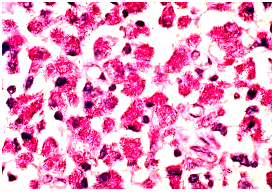

Rare diseases like Pneumocystis carinii, a tiny one-celled protozoa, filled gay lungs to the point of suffocation and requests for pentamidine aerosols to combat Pneumocystis trickled, and then poured into the CDC. Another uncommon killer, Kaposi’s Sarcoma [KS)of the skin, became the most common form of this gay-related immune deficiency.

Kaposi’s Sarcoma. Black arrows point to rounded tubercular microbes shaped as cocci and granules in the tissue.

That AIDS could be sexually transmitted was incontrovertible, through the gay sexual activities of Gaëtan Dugas alone. Dugas, a French-Canadian male air stewardess, was responsible for infecting at least 40 different men either by himself or through other men that had had contact with him. And of the 248 cases known before the detection of the virus, in excess of 40 of these AIDS victims had direct or indirect contact with Gaëtan Dugas.

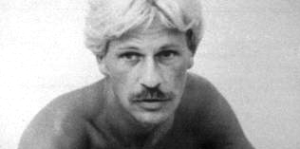

Dugas, who was on a collision course with history, only became sexually active in 1972. Born February 20, 1953, he would soon acquire the infamous name of Patient Zero.

Gaëtan Dugas: at one point said to be patient zero of the North American AIDS Pandemic.

On October 31, 1980 – ominously enough, Halloween night – the gay male airline steward Gaëtan Dugas visited a gay bathhouse for the first time on a layover in New York City. There it is speculated that Dugas caught the disease first. Sometime later, after having casual sex in a darkened room, a male interviewee later reported that when he had turned on a light in the room where Dugas lay, he spotted the lesions (Kaposi’s sarcoma) that were the classic earmarks of “gay cancer” on Dugas’ chest. When he remarked about it, Dugas replied sardonically, “It’s gay cancer. Maybe you’ll get it.” And so Gaëtan Dugas, the narcissistic and embittered flight attendant, was given the code name “Patient Zero”, though he was indeed not the first to contract AIDS. AIDS now had a face.

Kaposi’s Sarcoma- Papular type.

Nor was it only gays at risk. Drug addicts sharing needles and hemophiliacs, given pooled clotting factor VIII from blood so they would not bleed to death, soon became prey, again developing Kaposi’s sarcoma and pneumocystis pneumonia. America’s entire blood supply was in jeopardy, for by the early 1980s, gay and bisexual men accounted for 1 of 4 American blood donors.

AIDS throttled the immune system, in some cases shutting it down, and the primary site of attack always seemed traceable to the body’s T-cells: white blood cell lymphocytes which held the body’s invaders at bay.

By 1977 much evidence indicated that the basis of cellular immunity was tied in with T-cells lymphocytes — colorless, motile, cellular elements of lymph. Chief in importance among these was the T-helper or CD4 lymphocyte, which fought infection. It soon became apparent that in AIDS CD4 cells were either severely depleted or they fell off the blood map altogether.

Panic stricken virologists and other epidemiologists worked feverishly to isolate the source of this sexually transmitted disease whose first endemic wave washed upon American homosexual men’s shores. Without delay, these same virologists, who for decades had failed miserably to find a retroviral cause for cancer, pounced on AIDS, dismissing any possibility other than a virus or a retrovirus: ignoring that it could just as easily be either one or a combination of older microbes presenting in an all-new way. Among them – Robert Gallo and Luc Montagnier.

Virologists initially told physicians to pass on the word that it was the Cytomegalovirus [Ibid] that caused AIDS. Doctors dutifully obeyed, not fully realizing that all people, with time, are infected with Cytomegalovirus.

Epidemiologist/retrovirologist Donald Francis, who would direct laboratory efforts for AIDS at the CDC, and was also assistant director of the CDC’s Division of Viral Diseases — had his own peculiar theory. Oddly enough, it was one also shared with epidemiologist James Curran, eventual director of AIDS research at CDC. It went like this: combine hepatitis with feline leukemia in cats—a retrovirus on which Francis wrote his doctorate — and you had Kaposi’s Sarcoma and the opportunistic infections seen in AIDS. Or maybe, just maybe, it was a retrovirus similar to the cat retrovirus — which in and of itself, alone, was solely responsible. Curran and Francis had worked together years ago developing the Hepatitis B vaccine. They had all the connections in the scientific world that they needed.

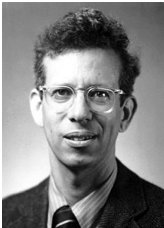

Donald P. Francis, M.D., D.Sc.

Francis, one of the few at CDC who had actively wiped out smallpox worldwide, was considered an expert on both epidemics — and the cat leukemic virus. He would now combine his fields of ‘expertise’, quickly concluding that AIDS was cat leukemia in people. It was an impulsive long shot, and by most treated as such — at least initially.

REFERENCES

- MMWR, Morb Mortal Weekly Rep 30:250–2. 1981.

CANCER STRUGGLES

America, Turn of the century.

Indeed, the history of retroviruses mirrored cancer research.

In1904, Ellermann and Bang, searching for an infectious bacterial cause for chicken leukemia [4], succeeded in transferring it from one fowl to another by injecting cell-free tissue infiltrates. They sought a bacteria, but simply because it passed through a filter, the responsible agent was assumed to be a virus.

That same year, the first lentivirus, later claimed to be related to HIV, was isolated as a filterable equine infectious agent in horses by Valle and Carre at the Pasteur Institute. [16] Yet Roux, an authority on ‘invisible microbes’ at that time, shrugged off Valle and Carre’s finding as no more than ‘small bacteria’. [14]

Most authorities now realize that there are some viruses almost as large as bacteria and some bacteria as small as viruses, forms of which can easily pass through filters. This realization was quickly disputed by HIV enthusiasts Francis et al. [5], when they falsely mentioned ‘since the infectious agent had obviously passed through a filter, it had to be a virus.’

It did not.

Peyton Rous was credited with the discovery and isolation of the first retrovirus. By 1911, Rous wanted to know why if one chicken got cancer, others followed. [13] Rous, who reproduced the tumor at will in Plymouth Rock fowls, favored a bacterial cause over a filterable virus. However, it was a question that he never definitely answered.

Dr. Francis Peyton Rous (1879-1970),

By 1933 Shope reported a viral tumor in cottontail rabbits, and Bittner reported on a milk-born mouse breast cancer attributed to still another virus. [1]

In fact by the1950s, and with the advent of the electron microscope, particles later questionably ascribed to retroviruses were readily being detected. As a result, and at a time when established medicine had about-faced and was now firmly set against an infectious cause for cancer, two controversial minority camps splintered from mainstream, each diametrically opposed.

There were the virologists, who claimed that cancer was viral or retroviral. And another group whose careful, peer-reviewed research, demonstrated that the retroviruses in Rous, Bittner and Shope tumors were actually filterable forms of mycobacteria. [10] Tuberculosis-like, these ‘viruses’ stained with acid-fast dyes; readily passed through a filter, but actually were a class of bacteria having many of the characteristics of mycobacteria such as tuberculosis.

This work, spearheaded by physician-researcher Virginia Livingston of Rutgers [9], validated earlier work on Rous as a bacteria. [3,6] But soon others would join [2,7,15]. Livingston’s network, questioning the very existence of retroviruses, and the retrovirologists did not like it. A scientific life-and-death cancer struggle ensued.

By 1960, biologist turned retrovirologist Howard Temin sought to contrive an explanation for his observation as to why retroviruses, composed of RNA, Rous among them, were inhibited by Actinomycin D — an antibiotic and known bacterial DNA inhibitor. Based on this finding, Temin elaborately hypothesized the concept of reverse transcription with its “reverse transcriptase”. But, in truth, since antibiotics did not affect viruses, Temin’s observation regarding Actinomycin D’s inhibition of Rous still made more sense if the Rous retrovirus was bacterial to begin with. It was later shown that Temin’s reverse transcriptase was also utilized by other microbes, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

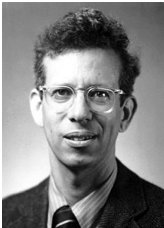

Howard M. Temin, PhD

Nevertheless, quickly capitalizing on the flawed logic of Temin, cancer viral investigators of the 1960s and 1970s reacted by conveniently misinterpreting his non-specific enzyme discovery [reverse transcriptase], which in fact arose primarily as either a function of normal cellular healing, or could be found in other pathogens — as a primary indicator for the newly scrutinized retroviruses. It was as a direct result of Temin’s enzyme, that ‘oncoviruses’, purported to cause cancer, suddenly became known as ‘retroviruses’.

It was to Rutger’s researcher Virginia Livingston’s solid disadvantage that when Richard Nixon signed his National Cancer Act on December 23, 1971, he unwittingly placed virologist Frank J. Rauscher Jr. as director of the just established National Cancer Program (NCP).

Dr. Frank J. Rauscher Jr.

With Rauscher at the controls it was only a matter of time before cancer virologists, retrovirologists and immunologists were pushed to the vanguard of ‘America’s War on Cancer’. Once entrenched, they would remain at the helm even as, incredibly, their failed cancer attempts now morphed towards finding the retroviral cause for AIDS.

Bacterial L-forms, the connecting link between viruses and bacteria, were first described by Emy Klieneberger at England’s Lister Institute, for which she named them “L-forms”. Such bacteria were ‘cell-wall-deficient’ (CWD) because they either had a disruption or lack of a rigid bacterial cell wall. This lack of rigidity allowed them the plasticity to assume many forms (pleomorphic), some of them viral-like but all of them different from their classical parent. Such forms were also poorly demonstrated by ordinary staining, [8] and many of them, just like viruses, easily passed the finest of filters. Of all the bacteria, it is tubercular L-forms that predominate and are crucial to the survival of tuberculosis and the mycobacteria. It is mostly in its cell-wall-deficient (CWD) forms, that TB can escape destruction by the body’s immune system. And at the same time CWD forms of the tuberculosis-like mycobacteria react in Elisa blood tests [11], similar to the ‘HIV retrovirus’, which they can simulate in every way.

Some years later, when HIV discoverer Luc Montagnier was interviewed for a French AIDS documentary, film-maker Djamel Tabi asked how he had isolated HIV. Incredibly, Montagnier’s reply was that he did not isolate HIV, he just found something that looked like a retrovirus. [12]

Klieneberger, as well as Livingston, also saw parallels between the filterable forms of tuberculosis and ‘mycoplasmic-like forms’ because without intact cell walls the mycobacteria were often mistaken for the virus-like bacteria mycoplasma, which has no cell wall. [8] The differentiation between mycoplasma and cell-wall-deficient bacteria, reported Mattman, was difficult at best. [11]

1. Bittner J. J. Some possible effects of nursing on the mammary gland tumor incidence of mice. Science 1936; 84: 162.

2. Diller I. Donnelly experiments with mammalian tumor isolates. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1970; 174(2): 655–674.

3. Duran-Reynals F. Neoplastic infection and cancer. Am J Med 1950; 8(4): 440–511.

4. Ellermann V., Bang O. Experimentelle Leukamie bei Huhnern. Zbt Bakt 1908; 46: 595–609.

5. Francis D. P., Curran J. W. Essex M Epidemic acquired immune deficiency syndrome: epidemilogic evidence for a transmissible agent. J Natl Cancer Inst 1983; 71: 1–4.

6. Glover T., Scott M. A. Study of the Rous Chicken Sarcoma No.1. Canada Lancet and Practicioner 1926; 66(2):49–62.

7. Alexander-Jackson E. A specific type of microorganism isolated from animal and human cancer: bacteriology of the organism. Growth 1954; 18: 37–51.

8. Klieneberger-Nobel E. Origin, development and signifincance of L-forms in bacterial cultures. J Gen Microbiol 1949; 3: 434–442.

9. Livingston V. A. Specific type of organism cultured from malignancy: bacteriology and proposed classification. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1970; 174: 636–654.

10. Livingston V. Cancer: A New Breakthrough. Los Angeles: Nash Publishing, 1972.

11. Mattman L. Cell Wall Deficient Forms – Stealth Pathogens. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 1993.

12. Null G. AIDS: A second opinion. Townsend Letter for Doctors and Patients, June 2000.

13. Rous P.A. Sarcoma of the Fowl transmissible by an agent separable from the tumor cells. J Exp Med 1911; 13: 397–411.

14. Roux E. Sur les microbes dits inviibles. Bull Inst Pasteur 1903; 1: 7–12, 49–56.

15. Seibert F. B., Feldman R. L. Morphological, biological, and immunological studies on isolates from tumors and leukemic bloods. N Y Acad Sci 1970; 174(2):690–728.

16. Vallee H., Carre H. Nature infectieuse de l’anemie du chevale. CR Acad Sci Paris 1904; 139: 331–333.

SHYH-CHING LO

Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, 1989

Dr. Shyh-Ching Lo, MD was a senior scientist at the prestigious, world-renowned Armed Forces Institute of Pathology in Washington. As he watched events unfold, and it became obvious that it was going to be dictum that HIV caused AIDS, he just had one problem: whenever he examined someone who had died of AIDS, he could never find HIV, not even a trace of HIV-infected tissue damage. So Lo began his own search for an AIDS cause which led him to a ‘virus-like infectious agent’. [8] Knowing he was onto something, Shyh-Ching Lo followed his conscience, against the grain of most other scientists, and finally isolated not a virus but a mycoplasma. And in one study of 24 people with AIDS, he found antibody titers to it in practically everyone. [9] Shyh-Ching Lo would co-published again, with Saillard. [13]

Shyh-Ching Lo, MD, about to give a presentation regarding Recent Studies of Epidemiology of MLV-related Human Retroviruses.

That same year Livingston died and a year later Luc Montagnier, the discoverer of HIV, almost got booed off a 1991 San Francisco podium by HIV activists at the Sixth International AIDS conference — for endorsing Lo’s mycoplasma as a necessary co-factor for the AIDS virus to become fatal. [10]

Montagnier and Lemaitre had done a hornet’s nest of an experiment which put HIV activists on the edge of their chairs. In 1990 the two scientists published that cells cultured with ‘HIV’, which normally died, grew well in the presence of two antibiotics, minocycline and doxycycline. [5] Antibiotics do not affect retroviruses, so they were not working against HIV – it was a bacteria. Montagnier decided that that bacteria was probably Lo’s mycoplasma. He had done so, unaware of the fact that the two particular antibiotics he was using also had activity also against Livingston’s atypical tuberculosis. [3,12,14,15] In the meantime Mattman made her claim that, even under the best of circumstances, it was difficult to differentiate certain mycoplasmas from cell-wall-deficient tuberculosis.

Rutgers-Presbyterian Hospital Laboratory for the Study of Proliferative Diseases, Bureau of Biological Research, Rutgers University, New Jersey, 1950

Livingston associate and prominent Cornell microbiologist Eleanor Alexander-Jackson [1], a lifelong colleague, had a problem. As long as Alexander-Jackson held her reputation as one of the leading tuberculosis experts in the world, American medicine embraced her, but when she tried to attribute cancer to Livingston’s tuberculosis-like germ, it would move to crush her.

Alexander-Jackson, whose advanced mycobacterial staining and culture techniques appeared in a 1944 issue of Science, carefully set a trap insured to ensnare virologists. Rous, as a retrovirus, was supposed to be an RNA virus. So Alexander-Jackson knew that finding DNA in it would automatically mean that it was bacterial. It was understood that Retroviral DNA should be present only in human or animal cells and nowhere else. But Alexander-Jackson’s paper on the ‘Ultraviolet Spectrogramic Microscope Studies of Rous Sarcoma Virus Cultured in Cell Free Medium’ demonstrated that there was DNA present in this Rous, characteristic of bacteria. [2] Why was it still being called a retrovirus?

When Livingston confronted Rous that his ‘retrovirus’ could be dried, shelved, stored and mixed months later in saline only to grow out on bacterial culture plates, he reminded her that he had never said it was a virus, carefully using ‘tumor agent’.

Dr. Virginia Livingston, MD.

To be certain, the Livingston network concluded that oncogenic, supposedly cancer-causing viruses, were in fact L-forms of tuberculosis-like mycobacteria and related organisms. And Livingston was coming much too close to proving her point to suit American retrovirologists.

Dr. Robert Gallo

Threatened by Livingston and Alexander Jackson’s findings, HIV co-discoverer Robert Gallo huffed:

‘What is going on in this country? This is insanity! She can have her theories and what can I say? I don’t know of anything to support it. I can’t see any basis and I don’t know what to say or what analogy to give you’. [11]

But Livingston’s findings, with worldwide stature, were not about theories of retroviruses yet to be isolated. She had, in fact, come much closer than any of the retrovirologists in proving a direct causation between her organism and cancer by showing that her germ manufactured human growth hormone (HCG), long associated with malignancy. [7]

Before her death, Livingston would give one more clue towards unraveling what had become AIDS. There were ‘less known’ and ‘little publicized’ microorganisms that were transmitted sexually. Through bacteriological studies she had confirmed that the very same L-forms of tubercular mycobacteria she found in Rous, by some called mycoplasma, could be found in the semen of man. [6]

1.Alexander-Jackson E. A. Specific type of microorganism isolated from animal and human cancer: bacteriology of the organism. Growth 1954; 18: 37–51.

2.Alexander-Jackson E. Ultraviolet spectrogramic microscope studies of Rous Sarcoma. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1970; 174(2):765.

3.Burns D. N., Rohatgi P. K. Disseminated Mycobacterium fortuitum successfully treated with combination therapy including ciprofloxin. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990; 142(2): 468–470.

4.Gupta I., Kocher J. Mycobacterium haemophilum osteomyelitis in an AIDS patient. N J Med 1992; 89(3): 201–202.

5.Lemaitre M., Guetard D. Protective activity of tetracycline analogs against the cytopathic effect of the human immunodeficiency viruses in CEM cells. Res Virol 1990;141(1): 5–16.

6. Livingston V. Cancer: A New Breakthrough. Los Angeles: Nash Publishing, 1972.

7.Livingston V., Wuerthele-Caspe, Livingston A. F. Some cultural, immunological and biochemical properties of progenitor cryptocides. Trans N Y Acad Sci Ser II 1974;36(6): 569–582.

8. Lo S. C. Isolation and identification of a novel virus from patients with AIDS. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1986; 35(4), 675–6.

9. Lo S. C., Dawson M. S. Identification of Mycoplasma incognitos infection in patients with AIDS; an immunohistochemical, in situ hybridization and ultrastructural study. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1989; 41(5): 601–616.

10.Ostrom N. Co-discoverer of AIDS virus says it may have microbial accomplice. New York Native 1991; October 21.

11. Parachini A. New ‘cure’ for cancer stirs controversy. Los Angeles Times 1984; April 6.

12. Roussel G., Igual J. Clarithromycin with minocycline and clofazimne for Mycobacterium avium intracellulare complex lung disease in patients without the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. GETIM. Groups d’Etude et de Traitement des Infections a Mycobceries. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 1998; 2(6): 462–470.

13.Saillard C., Carle P. Genetic and serologic relatedness between Mycoplasma fermentans strains and a mycoplasma recently identified in tissures of AIDS and non-AIDS patients. Res Virol 1990; 141(3): 385–395.

14.Tasaka S., Urano T. A case of Mycobacterium fortuitum pulmonary disease in a healthy young woman successfully treated with ciprofloxacin and doxycycline. Kekkaku 1995; 70(1): 31–35.

15.Tsukamura,M. Chemotherapy of lung disease due to Mycobacterium avium–Mycobacterium intracellulare complex by a combination of sulfadimethoxine, minocycline and Kitasamycin. Kekkaku 1984; 59(1): 33–37.

IN THE SEMEN OF MAN

Although tuberculosis was and still is, in scientific off-the-record fashion rarely spoken of as a sexually transmitted disease, the potential for this has always existed. In the presence of prostatitis, it may be transmitted through the semen. [20]

As long as the mysterious killer behind AIDS remained comfortably within the gay community not much was done to truly investigate it. As soon as AIDS found its way into the heterosexual population, though, suddenly America’s interest in ferreting out the cause of AIDS became paramount.

Anyone who watched AIDS evolve in not only gay America but heterosexually in Africa and Asia could not help but be struck by its travel and spread along the epidemiologic highways of sex, drugs, migrants, prostitutes, bath houses and venereal disease clinics. Yet the realization that sexual transmission of AIDS could occur between a man with risk factors and a woman came late. [3] Soon thereafter, female to male transmission, originally thought unlikely, was also found to occur. [29] By 1984, the pivotal importance female prostitutes played in the propagation of AIDS in equatorial Africa had become evident. [33]

But despite the magnifying forces of high tech tests such as the Polymerase Chain Reactors [PCRs], protein broths which make multiple copies of hard to find pathogens, its use in AIDS was never clear. Critics contested PCR vastly exaggerates “HIV” by making numerous copies of fragments of nucleic acid which might or might not even be HIV to begin with. And HIV itself could only be detected in a distinct minority of semen samples: one in 25. [34]

On the other hand, ignored and unnoticed, the very real possibility of the genital transmission of M. tuberculosis, a disease affecting almost 2 billion people, intimately linked with and considered a reliable sign of AIDS. [4,5] and frequently found in the genitourinary tract. [38]

The Research Center for Genitourinary Tuberculosis, Kingsbridge Veterans Hospital, Bronx New York, 1954

For 25 years, Dr. John K Lattimer, MD was a professor and chairman of the urology department at the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University.

By 1954, a pattern had emerged at Dr. John Lattimer’s Center for Genitourinary Tuberculosis. Men who developed tuberculosis epididymitis [inflammation of the testicles] were usually found to have an active focus of tubercular infection in their prostate and cultures of their semen were frequently positive for tubercle bacilli. [20]

But while documenting sexual transmission, what puzzled John Lattimer most was why more husbands with prostatic TB were not infecting their wives. Two possibilities came to mind. First, the resistance of the thick stratified vaginal epithelium to tubercular infection; second, the scorched earth policy of prostatic tuberculosis, whereby it sought to destroy glandular elements of the prostate [Ibid], severely decreasing semen volume. Many of his male patients, in fact, complained that orgasm produced only slight moisture at the tip of their penis with over half of his experimental group having a semen volume of less than 0.5cc — too scanty to infect the vaginal or vulvar epithelium, if it reached them at all. As almost a testament to this finding — of 40 men with tuberculous genital infections, only one produced a child. [Ibid]

Nevertheless, seeing sexual spread in a disease with staggering numbers right in front of him, he gave notice to the scientific world. [20] But few listened and adequate descriptions of tuberculosis as a sexually transmitted disease never really reached medical texts. Despite this tuberculosis is often unofficially listed among or with the sexually transmitted diseases.

Niagara Penisula Sanatorium, St. Catharine’s, Ont., Canada, December 1954

Dr. Edgar T. Peer was more than a bit skeptical as he reviewed Lattimer’s study regarding the seminal transmission of tuberculosis.

He himself had recovered tubercle bacilli from a patient’s semen in1952, but dismissed it as lab error. He would later write that like most dismissals of the tubercle bacilli on similar grounds, it would come back to haunt him.

Dr. Edgar T. Peer

By 1954, Peer’s cases of sexually transmitted tuberculosis were mounting and struck by similarities beyond coincidence, he saw an ‘extremely probable source’ of tuberculosis coming from the male genital tract.

Peer published, warning that if physicians did not wake up to the possibility of sexually transmitted genital tuberculosis, its diagnosis would continue to be unsuspected and underestimated, [28] which one day could lead to potentially catastrophic consequences.

Nor were Peer and Lattimer alone. Netter mentioned that the spread of the tubercle bacilli through the female genital tract of the tubercle bacilli by coitus with a tuberculous male could not be denied. [26] In fact, wherever culture of the seminal fluid showed Mycobacterium tuberculosis, there was a possibility of transmission of genital tuberculosis from male to female via the semen through sexual intercourse. [6] While Lattimer [21]and Peer [28] showed that the development of tuberculous ulcers in the vagina or vulva resulting in swollen lymph nodes in the groin was due to semen positive males harboring M. tuberculosis — Hellerstrom clocked the actual incubation period from the date of coitus during which the wife was exposed — to the development of a vaginal or vulvar ulcer and enlargement of inguinal lymph nodes — to approximately three to four weeks. [14]

Tuberculosis of the vulva

Heins then offered a better idea of the potential potency of sexually transmitted mycobacteria such as tuberculosis, demonstrating that even the tame Mycobacteria smegmatis, found in the smegma of the genital secretions of every man and woman alive — when introduced into the vaginas of female mice — resulted in the immediate death of over half of an experimental group of fourteen. [13]

Lattimer’s cases were compiled from European and American literature. The ulcer and enlarged nodes in the female, often misdiagnosed, closely resembled lymphogranuloma inguinale, syphilis or chancroids [Ibid] — all diseases that could coexist with tubercular sexually transmitted disease. [20]

And, just as men could transmit mycobacterial tubercular disease to women, so too could women infect men. [21] By1870 Soloweitschnick had documented the first observation of a tuberculous ulceration of the penis. [2]

Lewis cites 110 cases of tuberculosis of the penis written up before 1946. Twenty-nine additional cases were subsequently reported by Lal. [19] In his series of primary cases, Lewis pointed to 14 of venereal origin —12 penile ulcerations being definitely the result of coitus and two as a result of oral sex. [21]

Penile ulcer from tuberculosis

Penile ulcers, newly attributed to primary HIV, [15] were already well documented in TB literature [16,17,21,37]. And the ‘giant cells’ claimed to originate from HIV [22,30] were decades ago seen at the base of these ulcers. [21] Long a hallmark of tuberculosis, multinucleated giant cells form in the tissues and engulf the tubercle bacilli in an attempt to kill them. [23]

Lewis mentions that of all the ways in which the penis could be infected with tubercle bacilli, direct contact was by far the most common. Although he documented transmission mostly through vaginal sex and occasionally oral sex, rectal transmission was not explored. [21]

To explain cases claimed not to arise from direct vaginal inoculation, woman to man, Lewis borrowed from Verneuil’s hypothesis, somehow overlooked by later writers. In 1883, Verneuil, in “Hypothesis On the Origin of Genital Tuberculosis In The Two Sexes”, proposed a mechanism whereby men with infected urine or semen first inoculated the vaginal vault of their partners, and then, through subsequent sex became themselves re-inoculated at the corona or frenulum of their own penises [35]. Years passed. But voices of warning persisted.

By 1972, five years before gays started dying in the U.S., Rolland wrote “Genital Tuberculosis, a Forgotten Disease?”. [31] And ironically, in 1979, on the eve of AIDS recognition, Gondzik and Jasiewicz showed that even in the laboratory, genitally infected tubercular male guinea pigs could infect healthy females through their semen by an HIV-compatible ratio of 1 in 6 or 17%, prompting him to warn his patients that not only was tuberculosis probably a sexually transmitted disease, but also the necessity of the application of suitable contraceptives such as condoms to avoid it. [12]

Gondzik’s solution and pre-AIDS date of publication are chilling; his findings — too significant to ignore. Even in syphilis at its most infectious stage, successful transmission in humans was possible only in 30% of contacts. [32]

Two years later, investigators in South Africa, itself perched on the precipice of its own devastating sexually transmitted AIDS epidemic, issued a report of 91 cases of tuberculosis of the penis. [25,36] This was followed by documentation in which ‘HIV’ in young African females came only after first contracting genital TB. [11]

Moreover, the fact that Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare — also known as fowl or swine tuberculosis, and considered an ‘atypical’ tuberculosis — could also act like a sexually transmitted disease, set up an explosive scenario. [8–10]

Avium had, in the short space of 30 years, gone from relative obscurity to the leading infectious disease in U.S. AIDS. And despite the fact that DePaepe’s group used only conventional Ziehl-Neelsen tubercular stain without culture of either testicular tissue or semen, they still found M. avium in these specimens in 32% of AIDS patients with systemic M. avium — the same M. avium that would eventually kill most U.S. AIDS patients that did not die from other AIDS-related disease. [27]

Queens Hospital Center, Long Island Jewish-Hillside Medical Center, Jamaica, New York, 1984

Dr. Pascal De Caprariis saw a dying 30-year-old Haitian man with AIDS before him. A biopsy of the lymph node in the patient’s groin showed Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare [fowl tuberculosis] seemingly gone systemic — spreading to the liver. Despite using different combinations totaling seven different anti-tubercular drugs, the patient died. If ever there was a harbinger of things to come, this was it.

Then, just before the patient’s death an ulcerative lesion of the corona of the penis formed. Tests for herpes were negative. Upon culture, and only upon culture, Mycobacterium avium was isolated from the penile crater, and De Caprariis started speculating that with this and the his patient’s right groin lymphatic swelling, sexual transmission of Avium [fowl tuberculosis] seemed neither far-fetched nor improbable. [9]

Mycobacterium avium in lymph node tissue of an AIDS victim. Ziehl-Neelsen stain. Histopathology of lymph node shows tremendous numbers of acid-fast tubercular bacilli within plump histiocytes. CDC/Dr. Edwin P. Ewing, Jr.

Department of Microbiology, Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, 1985

Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, NY.

AIDS is what defined the decade of the 1980s, a decade that lived in fear beneath the partial shadow of a certain and tortuous death from a highly communicable pathogen.

But no one came closer to unlocking its true cause and mystery than American microbiologist Beca Damsker,MD. Damsker found overwhelming fowl tuberculosis infections of the colon and rectal tissues in U.S. gay AIDS time and time again — and knew that an anorectal portal of transmission had to be considered important in its transmission. Damsker was also picking up fowl tuberculosis in the buffy coat of the blood of recently acquired AIDS victims — that fraction of an anticoagulated blood sample that contains most of the white blood cells and platelets following centrifugation

Gay men had instinctively realized the implications of Damsker’s colon and rectal studies. Many had already made the intuitive leap that perhaps certain activities, such as anal intercourse, might be transmitting the causative agent. It was just that no one knew the specific agent being transmitted. Beca Damsker had just found that agent in fowl tuberculosis [Mycobacterium avium, or simply M. avium], but had no way of knowing how universal the process she was examining really was. But the regularity with which Damsker found Avium, also known as swine tuberculosis, in gay stool and lower intestinal biopsy specimens, stunned even herself. [8] Indeed, what she saw before her was a microcosm of the killer AIDS epidemic just outside her Mount Sinai research facility. Beca Damsker’s study was published in The Journal of Infectious Diseases in 1985.

Avium, or fowl tuberculosis, is a ubiquitous germ, found in animal reservoirs such as pigs, among others. [7] As to how AIDS originated in man, Damsker was not unaware of the possibility that a small subset of homosexuals had a proclivity for bestiality — sexual activities with animals — a potential vector for their transmission to man, which when combined with the fragility of the rectal mucosa to local trauma or intercourse and antigenic challenge, [24] could have led to calamitous unchecked multiplication of M. avium in gay AIDS, possibly of animal origin, in the intestinal mucosa and nearby lymph nodes. This then would set the stage for AIDS spread into the blood, with consequent targeting of other systems. [8] Damsker already had all the evidence she needed.

Tuberculosis in swine is almost always caused by M. avium [18] and such avian tuberculosis leads to some of the highest financial losses in the swine and poultry farm industry. [1]

Although fowl tuberculosis was thought of as an ‘opportunistic’ infection which occurred only late in the immunosuppression of AIDS, Damsker encouraged a closer look regarding the temporal relationship between fowl tuberculosis infection and the inception of American AIDS. In foreseeing this, Becca Damsker’s assessment of what doctors were picking up —as nothing other than a stepwise advance and increment of its causal germ — was squarely on target. From a rectal portal of entry, the germ merely progressed in ferocity and immunosuppression as the disease advanced and lowered CD4 counts. [8] Indeed, Becca Damsker, in speculating this, presented the single most plausible cause for American AIDS written to that point.

1. Berthelsen J. D. Economics of the avian TB problem in swine. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1974; 164: 307–308.

2. Brunati J. Tuberculosis of the penis; surgical form-case. Rev Chir Paris 1937; 75: 213–233.

3. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Immunodeficiency among female sexual partners of males with acquired immune deficiency syndrom (AIDS) – New York. Morb Mortal Weekly Rep 1983; 31: 700–1.

4. CDC Tuberculosis – United States, 1985 – and the possible impact of human T-lymphotropic virus type III/ lymphadenopathy associated virus infection. Morb Mortal Weekly Rep 1986; 35: 74–6.

5. CDC Diagnosis and management of mycobacterial infection and disease of persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Ann Int Med 1987; 106: 254–6.

6. Chakravarty S. C., Sircar D. K. Genital tuberculosis in males. Seminal fluid culture and vaso-seminal vesiculography studies. J Indian Med Assoc 1968; 51(6): 283–286.

7. Chapman J. S. The Atypical Mycobacteria and Human Mycobacteriosis. New York: Plenum Press, 1977.

8. Damsker B., Bottone E. J. Mycobacterium avium- Mycobacterium intracellulare from the intestinal tracts of patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: concepts regarding acquisition and pathogenesis. J Infect Dis 1985; 151(1): 179–181.

9. De Caprariis P. J., Giron J. A. Mycobacterium avium- intracellulare infection and possible venereal transmission. Ann Intern Med 1984; 101(5): 721.

10. De Paepe M. E., Guerrieri C., Waxman M. Opportunistic infections of the testes in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Mt Sinai J Med 1990; 57(1): 25–29.

11. Giannacopoulos K. C., Hatzidaki E. G. Genital tuberculosis in a HIV infected woman. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1998; 80(2): 227–229.

12. Gondzik M., Jasiewicz J. Experimental study on the possibility of tuberculosis transmission by coitus. Z Urol Nphrol 1979; 72(12): 911–914.

13. Heins H. C., Jr, Dennis E. J. The possible role of smegma in carcinoma of the cervix. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1958; 76: 726–735.

14. Hellerstrom S. Acta Dermato-Venereol 1937; 18(4): 465.

15. Hirschel B. In: Polsky, Clumeck (eds). HIV and AIDS. London: Mosby-Wolfe, 1999.

16. Jaisankar T. J., Bhagath R. G. Penile Lupus vulgaris. Int J Dermatol 1994; 33(4): 272–274.

17. Jeyakumar W., Ganesh R. Papulonecrotic tuberculids of the glans penis: case report. Genitourin Med 1988; 64: 130–132.

18. Karlson A. G. The incidence of tuberculosis in animals in the USA. Bull Int Union Against Tuberc 1968; 40: 61–63.

19. Lal D. N., Sekhon G. S. Tuberculosis of the penis. J Indian Med Assoc 1971; 56: 316–318.

20. Lattimer J. K., Colmore H. P. Transmission of genital tuberculosis from husband to wife via the semen. Am Rev Tuberc 1954; 69(4): 618–624.

21. Lewis E. L. Tuberculosis of the penis. Report of 5 new cases and complete review of the literature. J Urol 1946; 56: 737.

22. Lifson J. D., Reyes G. R. AIDS retrovirus induced cytopathology; giant cell formation and involvement of CD4 antigen. Science 1986; 232(4754): 1123–1127.

23. Livingston V. Cancer: A New Breakthrough. Los Angeles: Nash Publishing, 1972.

24. Mavligit G. M., Talpaz M. Chronic immune stimulation by sperm alloantigens. Support for the hypothesis that spermatozoa induce immune dysregulation in homosexual males. JAMA 1984; 251(2): 237–245.

25. Morrison J. G. L., Fourie E. D. The papulonecrotic tuberculide: from Arthus reaction to Lupus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol 1974; 91: 263–270.

26. Netter FH. Reproductive system. The Ciba Collection of Medical Illustrations. New Jersey: West Caldwell, 1987; 2: 188.

27. Nightingale S. D., Byrd L. T. Mycobacterium avium– intracellulare complex bacteremia in human immunodeficiency virus positive patients. J Infect Dis 1992; 165: 1082–1085.

28. Peer E. T. Genitourinary transmission of tuberculosis. Am Rev Tuberc 1957; 75: 153.

29. Piot P., Quinn T. C. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in a heterosexual population in Zaire. Lancet 1984; 2: 65–69.

30. Popovic M. Detection, isolation and continuous production of cytopathic retroviruses (HTLV-III) from patients with AIDS and pre-AIDS. Science 1984; 224(4648):497–500.

31. Rolland R., Schellekens L. Genital tuberculosis, a forgotten disease. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 1972; 116(52): 2377–2378.

32. Smith L. H., Wyngaarden J. B. Cecil Textbook of Medicine. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 1988.

33. Van de Perre P., Clumeck N. Female prostitutes: a risk group for infection with human T-cell lymphotropic virus type III. Lancet 1985; 2: 524–526.

34. Van Voorhis B. J., Martinez A. Detection of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in semen from seropositive men using culture and polymerase chain reaction deoxyribonucleic acid amplification techniques. Fertil Steril 1991; 55: 588–594.

35. Verneuil A. Hypothesis on the origin of genital tuberculosis in the two sexes. Gaz Hebt d Med 1883; 25: 225.

36. Wilson-Jones E., Winkelmann R. K. Papulonecrotic tuberculosis; a neglected disease in Western countries. J Am Acad Dermatol 1986; 14: 815–826.

37. Wood B. An unusual cause of penile ulceration. South African Med J 1991; 79(1): 284.

38. Wyngaarden J. B., 19th ed Cecil Textbook of Medicine; vol. 2. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 1992: 1740.

TRAGIC COST OF PREMATURE CONSENSUS

Pasteur Institute, Paris, January, 1983

The Pasteur Institute squeezed head of cancer virology, Luc Montagnier, into the pressure cooker of finding an AIDS retrovirus when its production of Hepatitis B vaccine, accounting for a significant part of its income, and in part processed from pooled American homosexual blood, came under fire. And frankly, they didn’t care how he “proved” it.

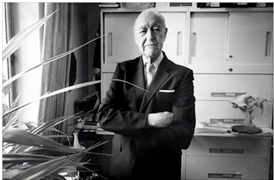

Dr. Luc Montagnier

Montagnier, who for his part was exclusively looking for a retrovirus related to Gallo’s failed HTLV-1, instead came upon the retrovirus “LAV” which, in wastebasket category fashion, stood for “Lymphadenopathy Associated Virus”. How did he know it existed? Because his assistant Françoise Barré-Sinoussi said that she found it……….or at least she found something that looked like it.

LAV was so named because the French homosexual fashion designer it was first isolated from had enlarged, inflamed neck nodes [lymphadenopathy], a common early AIDS feature. Thirty-three and promiscuous, he had also visited New York City in 1979, and had a 50-gay-partner-a-year history.

Betting the obvious — that the agent responsible for AIDS could be more readily detected in these swollen lymph nodes, Barré, in January, 1983, packed a small piece of the homosexual’s just biopsied lymph node en Toto in ice at Paris’s Pitie-Salpetriere Hospital and delivered it to Montagnier at Pasteur. This patient did not yet have full-blown AIDS, but his history and symptoms were strongly suggestive. [1] He would die 5 years later of the disease.

Montagnier and Barré-Sinoussi

At Pasteur, Montagnier put the tissue into cell cultures of T-lymphocytes. Immediately questions arose as to the procedure. Looking only for a retrovirus, the team cultured whole tissue lymph node lysates. The ‘virus’ was never isolated in its pure form. It would be the beginning of a long, long line of research work based on indirect evidence.

Later, looking at Montagnier’s tissue cultures microscopically there were many granules, some of which were felt to look like retroviruses. But they were inside cells and tissues – not whole viral particles — and had different shapes and sizes. No two were alike. They seemed to show all forms of ‘viral maturation’, but were they viral?

As early as 1928, Eleanor Alexander-Jackson began discovering unusual, and to that point, unrecognized forms of the TB bacillus. Jackson marveled at the many forms of tuberculosis, including the tiny granules which the German Hans Much saw in 1908, that soon became known as Much’s granules. [4] In 1910 Fontes proved that Much’s granules, as a sub-classification of Kleinberger’s L-forms, were filterable and therefore also often mistaken for viruses. In fact, in certain circles the variable acid-fast granules were called ‘the TB virus’. [2]

But even prior to Livingston [1970], Mellon and Fisher had warned that filterable forms of M. Avium andtuberculosis could easily be mistaken for the virus Montagnier and Barré thought they had [3] and might explain ‘the common finding by French workers of tubercular acid-fast bacilli in the glands of guinea-pigs into which viral-like [cell free] filtrates of tuberculosis material had been injected.’ [Ibid]

1. Barré-Sinoussi F., Chermann J. C. Isolation of a T-lymphotropic retrovirus from a patient at risk for acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Science 1983; 220: 868–871.

2. Fontes A. Bemerkungen uber die Tuberkulose Infektion und ihr virus. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1910; 2: 141–146.

3. Mellon, Fisher New studies on the filterability of pure cultures of the tubercle group of microorganisms. J Infect Dis 1932;51: 117–128.

4. Much H. Die Variation des tuberkelbacillus in form and wirkung. Beitr Klim Tuberk 1931; 77: 60–71.

THE RACE

Pasteur Institute, Paris, 1983

Institut Pasteur, Paris

Gallo’s leukemic retrovirus (HTLV), which Barré and Montagnier thought they had isolated, should have led to the wild proliferation of lymphocytes. But all that Françoise Barré-Sinoussi found in subsequent trips to the lab was how well it was slaughtering them. This deeply disturbed her, as retroviruses typically didn’t kill cells. How could she explain this?

By January 25th, 1983, Barré-Sinoussi’s reverse transcriptase radioactivity counter was clicking-away with increased activity, which to her, as a retrovirologist, meant that her lymph node ‘retrovirus’ LAV must be multiplying.

But reverse transcriptase was nonspecific and was also found elevated in events leading to the death of CD4 lymphocytes by tuberculosis [16], as well as in M. avium [fowl tuberculosis] infection of neck lymph nodes [2], probably the very event Françoise Barré-Sinoussi was watching. Again, why had she not considered these as a possible AIDS causes?

In actuality, previously having been retroviral cancer researchers, Barré-Sinoussi and Montagnier where solely attuned, intellectually and technologically to detecting “retroviruses”. Barré had been trained in mouse retroviral techniques requiring the measurement of reverse transcriptase in Robert Bassin’s National Cancer Institute (NCI) lab. Her procedures were not designed to explore for some unknown pathogen. In effect, Françoise Barré-Sinoussi and Luc Montagnier found a retrovirus because that was all that they were looking for.

Within weeks Montagnier called a staff meeting. The new ‘retrovirus’ wasn’t Gallo’s discredited HTLV-1, so everyone could breathe a sigh of relief. He also wasn’t asserting that his retrovirus HAV actually caused AIDS……..but it was possible. In the future he would send samples of the tissue culture to Gallo who headed AIDS research at NCI to stimulate further research.

Approximately one year later, after receiving French samples from Montagnier, retrovirologist Gallo isolated and announced that he felt that his newly isolated HTLV-3 retrovirus must cause AIDS — a retrovirus, which proved to a carbon copy of Montagnier’s LAV retrovirus………which he said was a productive Lentivirus infection with all forms of viral maturation.

A colleague had suggested that Montagnier characterize his virus as a Lentivirus [‘Lenti’ means slow] on a hunch. Lentiviruses were large viruses which, after entering cells, did not leap into activity at once, but later shot into action. But so-called “slow viruses” had been implicated, but never proven, in diseases such as Creutzfeldt-Jakob, and Alzheimer’s as well. Prominent American retrovirologist Peter Duesberg, who did much of the pioneer work on retroviral ultrastructure, knew that as direct pathogens the retroviruses were not ‘slow’ viruses. They were not even lentiviruses like Visna, with which HIV was often compared. Visna never acted like that. Rather, if Visna reached high enough blood concentration, Duesberg related, it was rapidly pathogenic. [10] HIV [Gallo’s HTLV-3 or Montagnier’s HAV] however, was not to be found in such high amounts in the blood. Perplexed, Duesberg concluded that there was no such thing as a slow virus, ‘only slow virologists’. [7] On the basis of his experience with retroviruses, Duesberg has challenged the virus‐AIDS hypothesis in the pages of such journals as Cancer Research, Lancet, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, and The New England Journal of Medicine.

Peter H. Duesberg Ph.D.

The discovery of LAV (HIV) allowed virologists to worm their way into taking the high ground in American medicine. No longer would practicing physicians like Livingston, who had seen disease face to face, assume leadership on policy issues. The new medical shamans would be laboratory gene splicers, molecular biologists, virologists and immunol- ogists, who told doctors what to think about conditions they never had ever clinically treated. A dangerous precedent was being set.

Cambridge University Clinical School, Cambridge, England, September, 1983

Former viral cancer researcher Abraham Karpas, worked out of the Department of Hematological Medicine at Cambridge. By September, 1983 he had identified a ‘transmissible agent’ through electron micrographs of the blood of a gay AIDS patient. [8]

Dr. Abraham Karpas

Karpas was having a problem with Gallo’s HTLV1 and was unable to confirm previous reports of this purported AIDS retrovirus in Africans. Many blood tests finding HTLV1 positive by previous investigators were found negative when retested in Karpas’s lab. [9]

Karpas, probably the second man in the world to see the AIDS agent, fired off a quick report on his transmissible agent complete with a microphotograph, but was having difficulty getting the paper published. He had the honesty to admit that he wasn’t certain that the 55 nm particles with their 10 nm electrodense cores were viruses at all, and began his paper with the phrase ‘assuming it is a virus’, though, whatever it was, he later found it identical to Montagnier’s “HIV”.

Experts in the field sided with Karpas’s restraint. Not only were retroviral particles ‘no proof that a virus was involved’, but such particles were ubiquitous – a statement supported by O’Hara’s Harvard study which found ‘viral particles, morphologically indistinguishable’ in 90% of the enlarged lymph nodes in both AIDS and non-AIDS patients. [13] O’Hara’s study stood out as the one study to date which used suitable controls, finding ‘viral particles’ indistinguishable from HIV in a variety of swollen lymph nodes without HIV.

Similarly, African studies of the lymph nodes of patients with HIV also showed them indistinguishable from those with just tuberculosis and without AIDS. [12,15] O’Hara concluded ‘The presence of such particles do not, by themselves, indicate infection with HIV’. Yet it was photomicrographs of the same particles which first informed the world that there was an HIV.

In Reproduction of RNA Tumor Viruses, Badar warned that in vitro cultures, even virus free, ‘can be induced to produce particles which resemble RNA tumor viruses in every physical and chemical respect’ [3], an event many saw applicable to the rigors and harsh processes Montagnier and Gallo put their AIDS tissues thru.

Oddly, it would not be until 1997 that two independent groups would examine these HIV particles in accordance with accepted international procedure. [6,4] Both teams saw an excess of fluid filled, many formed [pleomorphic] ‘contaminating’ vesicles, ranging in size from 50 to 500 nm as opposed to a minor population of particles of about 100 nm.

The latter were assumed to be viral, but proved, according to critics, to be too large, of the wrong shape and containing too much material to be retroviruses. In fact, both the particles and vesicles of Bess and Gluschankof share common antigenic determinants with and could easily have been the variably-acid-fast tubercular mycobacterial L-forms microphotographed by Seibert [14], Alexander-Jackson [1], Livingston [11] and Cantwell [5]. Livingston showed a protoplast of tuberculosis with L-form inclusions budding out vesicles from its surface not unlike the vesicles in the 1997 AIDS verification studies, while Seibert and Cantwell showed particles similar to those attributed to HIV. And the ‘substantial amount’ of both RNA and DNA found by in “HIV” vesicles, Bess found, points more toward a bacterial or mycobacterial origin.

Suddenly, it seemed as if the world had been sold a bill of sale on a non-existent retrovirus.

1. Alexander-Jackson A. Specific type of microorganism isolated from animal and human cancer: bacteriology of the organism. Growth 1954; 18: 37–51.

2. April M. M., Garelick J. M. Reverse transcriptase in situ polymerase chain readtion in atypical mycobacterial adenitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1996; 122(11):1214–1218.

3. Bader J. P. Reproduction of RNA humor viruses. Comprehensive Virol 1975; 4: 253.

4. Bess J. W. Microvesicles are a source of contaminating cellular proteins found in purified HIV-preparations. Virology 1997; 230(1): 134–144.

5. Cantwell A. R. Histologic observation of variably acid-fast coccoid forms suggestive of cell wall deficient bacteria in Hodgkin’s disease. A report of four cases. Growth 1981; 45:168–187.

6.Gluschankof P., Mondor I. Cell membrane vesicles are a major contaminant of gradient enriched human immunodeficiency virus Type-1 preparations. Virology1997; 230(1): 125–133.